9th May, 2018

I’d had a great couple of weeks. I’d just got back from visiting my Dad in Spain, along with my sister and beautiful niece (whom I had never met).

Spain had really inspired me this visit, and I dreamed of being able to take a bike to some of those pristine roads in Andalucia. Maybe next time.

A couple of weeks back home had seen the unusually long winter finally give way to rising temperatures, and the longer day allowed riding with friends after work again. I met my friend Shane for a short ride out and meal afterwards to see in the new riding season. During the ride I became aware of something in my left eye; what looked like a large vitreous floater; the kind of ghostly web that one sees occasionally, but much larger. Later on, in the pub, it came and went. I recall thinking that in a certain light it looked as if someone dressed in black was standing in my periphal vision. Due to a sense of optimism and well-entrenched morbid fear of hospitals and doctors, I thought I’d sleep on it and see how it was the next day. I wasn’t especially worried at this point.

Well, you’ve got some blood in there.

I awoke the next morning, and as soon as I sat upright that ghostly floater had turned an inky, impenetrable black. If you imagine your vision simplified as a rectangle, the bottom left-hand quarter was completely gone, replaced by a shapeless dark void.

Obviously this warranted a trip to the ER, which fortunately was just up the road. After handing over $100 (my ‘copay’) I was seen almost immediately. I described the symptoms and had to place a towel across my eyes, sit in the dark for ten minutes, and await the retinal scanner.

This machine, about the size of a coffee percolator, whirs and clicks as it locates your eye, then takes a picture. The ER doctor, a genial, middle-aged man looked at the images and said “Well, you’ve got some blood in there.” He suspected a ruptured blood vessel but was emphatic that he couldn’t say for sure. “We see about two per week. It’s common. Just not to you.” Fair enough, this was the ER, they were not going to be able to do much more. I needed to see a specialist at an eye centre as soon as possible, which as far as the ER were concerned meant the next day. There was no immediate urgency at this point; just a kind of calm hurry.

I called my local eye centre and was greeted by a receptionist with all the enthusiasm of someone that wished you were already dead. She told me they were full the next day, she’d have to ring around and would call me back (narrator: She didn’t call back). In the end I decided to call again and this time got someone useful that booked me in at a location the other side of town the next morning.

Sewickley, PA. 11th May, 1100hrs

Oh, that sounds like a retinal detachment. I hope not.

By this time, it had got worse. If I had to describe it in percentage terms, I’d estimate that around half the vision in the left eye was gone. I was scared, my family was scared, and I was starting to feel the onset of some panic. what could be wrong with me? Was it just my eye, or was something else happening?

The triage nurse was efficient, funny, and had a bedside manner that definitely needed a bit of work. She was also, as it turns out, right on the money. As I described my symptoms and she established what I could and couldn’t see by moving her hand around my field of vision, she casually uttered “Oh, that sounds like a retinal detachment. I hope not.” I could have lived without hearing the last sentence, but in hindsight (ho ho ho) I suspect she was referring to the fact this would not be a quick fix, rather than a gloomy prognosis. I was then left in the waiting room for an hour to ruminate (in an extremely anxious state, as you might expect) on what I’d been told. My eyes had some drops to dilate them, so I strained to read my phone (battery: 20%) to try and figure out just how much shit I was in, all the while sending nearly unintelligible text messages to my wife waiting outside with the kids.

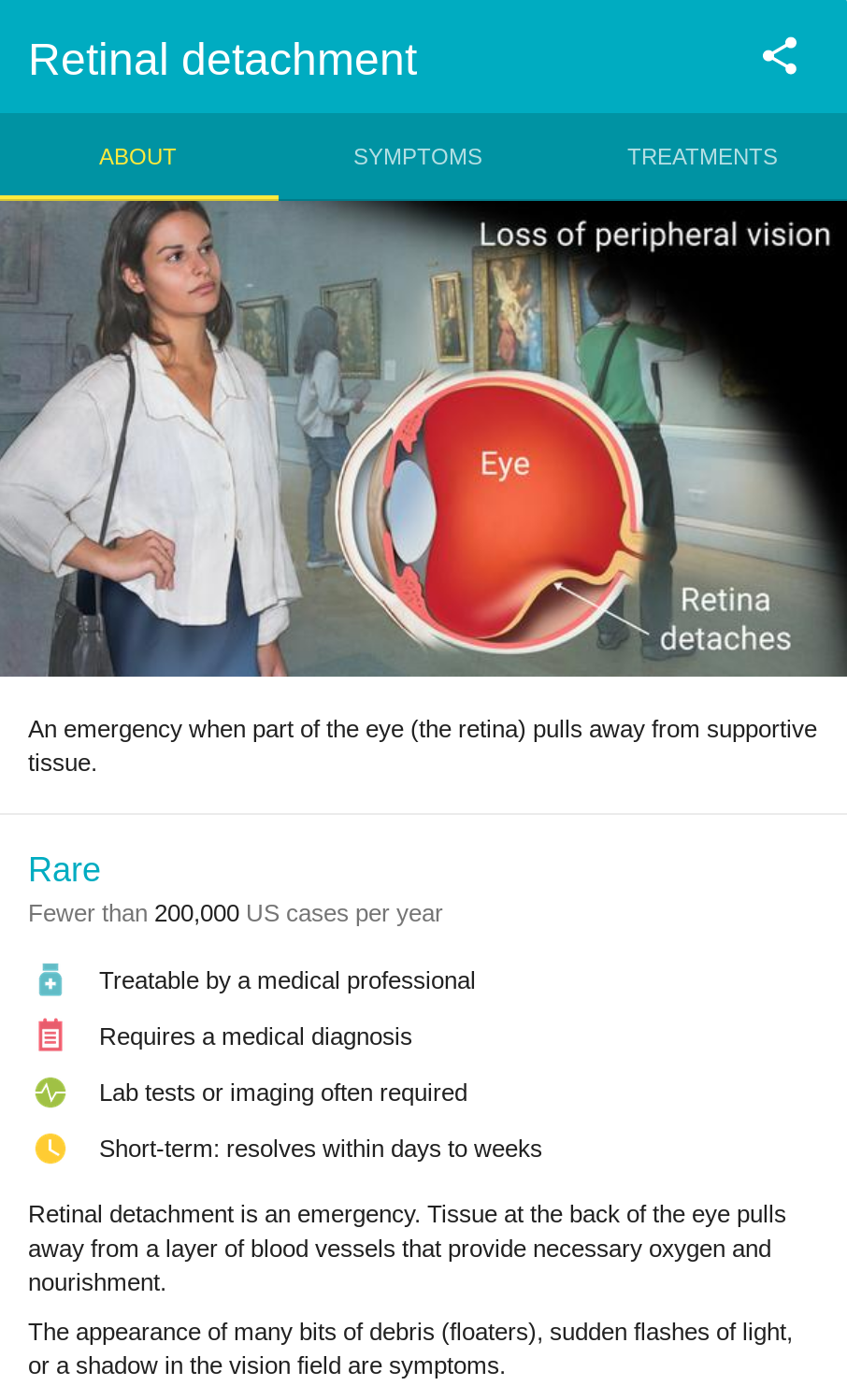

When the wait was over and I saw the ophthalmologist, she was absolutely brilliant, warm-mannered and confident enough to greatly reassure me, and confirmed the triage nurse’s suspicions: It was a retinal detachment. I had three small tears at 9,11, and 2 o’clock, the most common form, known as rhegmatogenous detachment. Why? Age and plain bad luck (National Eye Institute, 2009). It would require an operation, and the Dr. told me she would be calling around to find a surgeon, and that I was not to eat anything as the operation might be that day. It was at this point I realised this was fairly serious, but the nurse and doctor confidently assured me I would be fine.

Word came I was to head to UPMC Mercy for surgery immediately. My wife, cool as a cucumber under what must have been enormously stressful conditions with two children to look after, took me there straight away.

UPMC Mercy, 1445hrs

You’re sitting there, minding your own business, and your retina just decides to go and detach itself.

I’d been lucky. I’d never had surgery. First stop was pre-surgery testing, which would typically involve obtaining blood for analysis, but actually turned out to be nothing but verifying paperwork in my case. No blood work required. Then I was admitted which was a matter of bagging my clothes and belongings, donning a gown and letting the scrubs-wearing ninjas get me ready. The surgeon and the fellow assisting him (both absolutely brilliant guys) came to see me, and he introduced himself with a jovial “You’re sitting there, minding your own business, and your retina just decides to go and detach itself.” They both examined my eye and told me the plan: A sclerical buckle, and probably a vitrectomy, due to the number of tear sites. A sclerical buckle is a small band that is fixed around the circumference of the eye like a belt (hence the name), the purpose of which is to apply pressure and help reattach the retina. Due to the offset of one of the tears, it probably would not be sufficient on its own, so a vitrectomy would be required. This involves draining the vitreous; the gel-like liquid inside the eye which maintains the spherical shape. Two precision techniques, laser and cryopexy are used to bond the torn areas of the retina to the wall of the eye. A gas is then used to form a bubble temporarily replacing the vitreous (National Eye Institute, 2009).

The surgeon marked his initials just above my left eyebrow. He described this was necessary to mitigate what is considered a ‘never event’. I’ll let you guess what…

I’d lost track of time at this point. My pupils were profoundly dilated. My watch had been removed and I could no longer read the clock above the nurse’s station. I was wheeled off to the anaesthesia area to prepare for the op. After a chat with the anaesthetist and a great deal of questions I was rolled into the operating room. An oxygen mask went on, the IV was started, and shortly after that, the lights went out.

I came round with no pain, intense nausea, and a big old bandage over my left eye. I had my face in a horseshoe-shaped pillow; until my follow up appointment the next day it would be necessary to keep my head down so the vitreous gas bubble would maintain positive pressure against the retina (Retinadoctor, 2018). The nurses were fantastic; one of them put something in my IV to relieve the nausea and it stopped in a snap. I couldn’t quite read the clock so I wasn’t sure if it was 915pm or 245am. It was the former, thankfully. My wife and kids charged into the recovery room and I felt a lot better.

The nurses helped me into my clothes and I was on my way, almost 12 hours after the day had started.

Aftermath

As I write this, it’s one week later. The follow up appointments revealed the surgery had been successful, now it was a matter of waiting for everything to heal. I feel pretty fortunate, as I never had much pain and the swelling (which was profoundly unpleasant) reduced rapidly. The vitreous gas bubble has shrunk as it is slowly absorbed and replaced by vitreous fluid; I can clearly see its circular shape in my eye. My sight isn’t quite there, it’s rather fuzzy, but it is improving, and it is all there. Best of all I have my peripheral vision back on the left side; I can drive again and I don’t feel dizzy anymore. There is a possibility of developing a cataract as a result of the vitrectomy (NCBI, 2014), which will require further surgery, but I’ll deal with that down the line. It beats being blind.

Some things fall into perspective at a time like this. One of them is, if you have a problem with your eye, don’t fuck about. I should have got it looked at immediately. It may not have changed the outcome, but it could have made things easier, and the extent of sight loss would not have been so great. I’m also fortunate to have such a great wife. We have no help, it’s just us and one or two friends. My wife looked after everything.

Life is short. One moment I was out having fun with a friend, suddenly I’m looking down the barrel of sight loss. Isn’t it amusing how many of these metaphors involve sight? I can tell you my sense of humour has had quite a workout in the last week.

I’m not dying (well, no faster than anyone else), I didn’t go blind, I’ll probably ride my bike this week. I’m pretty lucky, all told.